By Kojo Kwarteng

On 31st May 2010, Ghana boldly enacted one of the world’s progressive legislations, “The Alternative Dispute Resolution Act, 2010 (Act 798).” The Act was to provide for the settlement of disputes by arbitration, mediation and customary arbitration, to establish an Alternative Resolution Centre and to provide for related matters.

Act 798 repealed the Arbitration Act, 1961 (Act 38) and modelled largely after the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) Model Law on International Arbitration of 1985 as amended in 2006. The Act which hinges on party autonomy, allows disputants the independence in drafting dispute resolution process to meet their context and recognizes the separability of arbitration agreements[1], thus, treating arbitration clauses distinct from the main agreement. Paul Kirgis’ opinion of the ADR Act 2010 captures the objective: “in recent years, Ghana has embarked on an experiment in the integration of traditional and state legal systems under the rubric of alternative dispute resolution. The primary vehicle for this experiment is the Alternative Dispute Resolution Act of 2010 (the Ghana ADR Act), an ambitious attempt to standardize the provision of commercial arbitration, mediation and customary arbitration nationwide[2].”

In its 14 years of operation, Ghana’s ADR Act has received national and international accolades and brought the law governing arbitration into harmony with international conventions, rules and practices, provided legal framework to facilitate and encourage the settlement of disputes through ADR procedures as well as achieve conflict resolution through a negotiated approach acceptable to all parties in a timely, efficient, cost-effective and non-adversarial manner. Through the Act, Ghana has earned recognition as the beacon of “judicial democracy” in Africa south of the Sahara and most of Africa. [3]

Ghana as a country, from the government, the judiciary, legal practitioners, traditional governance and ADR practitioners attach much premium to the ADR Act. The fact that 15th-19th July was declared ADR Week in Ghana by Her Ladyship, the Chief Justice, was a practical demonstration of commitment towards awareness creation by the judiciary and government. This is celebrated thrice (including March and November) in a year. The rationale for the celebration is to afford the ADR Directorate of the Judicial Service the opportunity to inform the citizenry of ADR as an integral part of the court system, its significance and to encourage the populace to take advantage of ADR. However, the July celebration of the week was almost overshadowed and thwarted by the strike action declared by organized labour, including the Judicial Service Staff Association of Ghana (JUSAG).

An array of reviews has been carried out by eminent jurists, lawyers, law lecturers, ADR practitioners and academics on the achievements and weaknesses of the ADR Act and its implementation. Among the reviewers which are easily accessible universally include those authored by Amegatcher, Nene (JSC as he then was) titled, “The Emergence of Alternative Dispute Resolution As A Tool For Dispute Resolution in Ghana[4]” and that of Torgbor, Edward, “Ghana’s Recently Enacted Alternative Dispute Resolution Act 2010 (Act 798): A Brief Appraisal.”[5]

The provisions on arbitration, customary arbitration and mediation as contained in Act 2010 are based on internationally recognized principles such as autonomy of the arbitration agreement and supremacy of the party autonomy. The Act also breaks new grounds in legislating on customary arbitration and granting the settlement agreement from mediation proceedings an enhanced akin to arbitral award. The Act, by all standards, is comprehensive, modern and forward looking and should enhance Ghana’s chances of being chosen as seat of their arbitration references within sub-Saharan Africa.[6] Frempong (2006) asserts that the ADR Act 2010 is a “recast of time-tested pre-colonial conflict resolution mechanism administered through the chieftaincy institution which sought to reconcile individuals and communities as well as improve social relations beyond mere settlement of disputes of conflicting parties[7].”

ADR Practice in Africa

Nigeria on 26 May 2023 enacted the Arbitration and Mediation Act 2023 (the ‘New Act’ or ‘AMA’),[8] to speed with the evolution of the global best practices in the arbitration and mediation ecosystem. This was 13 years after Ghana has enacted the 2010 Act. The repeal of the 35-year-old Arbitration and Conciliation Act of 1988 (the ‘ACA’ or ‘Old Act’) by the New Act signifies a significant legal transition. ADR in South Africa is not a new concept since 1960s with the country becoming a signatory to the 1958 New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards in 1976.[9] The promulgation of Arbitration Law No. 27 of 1994 was a milestone in providing comprehensive framework for encouraging arbitration and settling dispute related to investment and commerce [10]in Egypt. Rwanda in 2012 set up the Kigali International Arbitration Centre (KIAC) to attract, create opportunities for arbitration in Rwanda and neighboring countries. According to Agada John Elachi ADR in Togo has not experienced bliss or development compared to other African countries. However, like Ghana, Togo is one of the few African countries that maintains its heritage and takes pride in the Africa culture. In Kenya, ADR methods such as negotiation, conciliation, mediation and arbitration are prominent, and arbitration proceedings take between six months and three years[11].

Purpose of This Article

This article, does not intend to repeat the points in terms of achievements and inadequacies of the Act made by other reviewers, jurists, and academicians but to point out or to bring home the significant roles and contributions of chiefs towards the appreciation and growth of ADR mechanisms and procedures in Ghana and the sidelining of chiefs and traditional leaders or rulers in the composition of the ADR Board of Ghana by the Act and the state. It is also aimed at educating the masses on the role of the ADR Centre/Board and contribute to arousing the interest of Chiefs, the people and all stakeholders in ADR, particularly its growth in Ghana and beyond. The write-up further seeks to solicit the support of traditional leaders to join the campaigns to make ADR mechanisms number one choice in dispute resolution.

Inauguration of ADR Board

In July 2024, the President of the Republic inaugurated the Governing Council/Board of ADR Centre. The establishment of the ADR Board is provided for under section 117 of the ADR Act 2010[12] and comprises:

Section 117 (1) (a) [13] a Chairperson who is a lawyer of not less than twelve years standing

Section 117(1)(b) One member of each of the following, nominated by the respective body,

- i) Ghana Chamber of Commerce

- ii) the Ghana Bar Association

iii) the Institute of Surveyors;

- iv) Institute of Chartered Accountants; and

- v) a woman nominated by the President;

- c) one representative of organized labour;

- d) one representative from industry; and

- e) the Executive Secretary of the ADR Centre

2)The chairperson and members of the Board shall be appointed by the President in accordance with Article 70 of the Constitution.

Mr Alex Nartey, ADR Coordinator at the Judicial Service and Mr Daniel Owusu-Koranteng, President of the Ghana National Association of ADR Practitioners (GNAAPS), confirm that it is the first of its kind that the ADR Board has been constituted and inaugurated since the coming into force of Act 798[14] more than 14 years ago.

The Role of the ADR Board

The role of the ADR Board is provided for under section 117 (3) of Act 798[15] as “The Board shall perform the functions of the ADR Centre” which is mainly to facilitate the practice of ADR and will hold office for three years. For ease of reference, the ADR Centre is established by section 114 of the Act[16] as a body corporate with perpetual succession and a common seal and may sue or be sued in its corporate name.

Section 115 of the Act[17] sets the object and functions of the ADR Centre as follows:

- The object of the Centre is to facilitate the practice of alternative dispute resolution.

- For the attainment of its objects, the Centre shall

“(a) provide facilities for the settlement of disputes through arbitration, mediation and their voluntary dispute resolution procedures;

(b) exercise any power for alternative dispute resolution conferred on it by parties to a dispute but not be involved in actual resolution of the dispute; (c) keep a register of arbitrators and mediators;

(d) provide a list of arbitrators and mediators to persons who request for the services of arbitrators and mediators;

(e) provide guidelines on fees for arbitrators and mediators;

(f) arrange for the provision of assistance to persons as it considers necessary;

(g) from time to time examine the rules of arbitration and mediation under this Act and recommend changes in the rules;

(h) conduct research, provide education and issue publications on all forms of alternative dispute resolution,

(i) set up such regional and district offices of the Centre as the Board considers appropriate;

(j) register experienced or qualified persons who wish to serve as customary arbitrators and keep a register of customary arbitrators; and

(k) request the traditional councils to register and keep a register of persons who wish to serve as customary arbitrators.

From the provisions of the Act on the composition of the ADR Board, nowhere is the institution of chieftaincy or a representative of the National House of Chiefs or simply chiefs is mentioned. This, the writer submits, in all sincerity, may be an omission and unintentional on the part of the Legislator, after having read through the deliberations of the House on the Bill which ended on 24th March 2010[18].

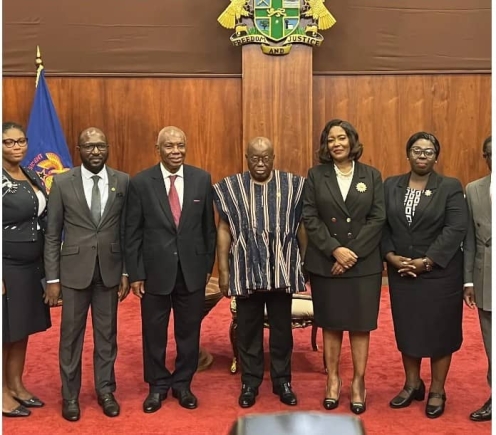

In accordance with the dictates of the Act, the President of the Republic on the 17th of July inaugurated the ADR Governing Council/Board at a ceremony, held at Jubilee House, which was attended by prominent figures including Chief Justice Gertrude Torkornoo and Attorney-General Godfred Yeboah Dame, along with justices from various judicial levels, the Bar President, and the Minister of Trade and Industry, K. T. Hammond.[19]

The Board is chaired by Justice Victor Jones Mawulorm Dotse (JSC as he then was), with Mrs. Efua Ghartey as a nominee.

Other members include Mr. Francis Kofi Korankye-Sakyi representing the Ghana Chamber of Commerce, Michael Gyang Owusu from the Ghana Bar Association, Jose Nicco-r Annan from the Ghana Institute of Surveyors, Angelina Mensah-Homiah from the judiciary, Ms. Joyce Adu from the Institute of Chartered Accountants, and Mrs. Philomena Aba Sampson representing Organized Labour. From the list, there is no traditional ruler unless the Board member uses his/her private title or name.

From the Parliamentary Hansard relating to the debate preceding the passage of Act 798, there was more unanimity and healthy relationships among MPs. The Parliamentary Committee which perused the draft bill on December 9, 2009 noted a number of positive developments to the Bill including the role of the ADR Centre and customary arbitration. In the previous edition of the Bill, the ADR “Centre was to provide facilities and manage the entire alternative dispute settlement process.” [20] The current Act confines the role of Centre to educating the public on the benefits of ADR process,…….as set out in section 115 of the Act. From the writer’s perspective, the role of the ADR Centre/Board is too narrow and does not allow for creativity and growth. From the principles of corporate governance, Board is expected to manage, supervise and control the affairs of the institution; Section 190(3) of Companies Act, 2019 (Act 992) and OKUDJATO and OTHERS VRS IRANI BROTHERS and COMMODORE VRS FRUIT SUPPLY GHANA LTD[21]. However,the ADR Act 798 is a specific legislation. The directors may have to exercise powers within the Act.

The contributions of Chiefs/Traditional Rulers to ADR

The nation continues to cherish and maintain ancient traditional values as exemplified by the institution of chieftaincy based on custom and usage. In the pre and post colonial Ghana, Chiefs, traditional councils and the Council of Elders were the most instrumental in matters of ADR. Chiefs presided over conflict cases brought or summoned up to the Palace while the Council of elders offered counselling roles to the chiefs. Adjudication of issues in the Ghanaian jurisdiction can be traced back to the pre-colonial era where powers were vested in chiefs, elders, and representatives of all the major tribes. Chiefs and elders adjudicated on most issues with the family heads serving as “lawyers”. Communities of the Gold Coast had elaborate and effective dispute resolution system. “Mediation, arbitration, negotiated settlements, to mention just a few, were the mainstream dispute resolution processes employed by the people to resolve their disputes.” [22]During the colonial era, judicial powers were vested in the Privy Council, which took away the powers of the chiefs and elders and systematically dismantled the traditional dispute resolution mechanisms with the “Native Courts.” At times parties to a dispute may want to resolve the dispute in a form other than the normal court system (litigation), hence ADR.

Chiefs in customary arbitration

Chiefs are the custodians of customary law, practices and traditions. They are the custodians of local traditions, customs and usage. “Thus, chieftaincy is the custodian of the customary values and norms of the nation; it is customary laws that regulate civil behaviour in traditional governance with judicial, legislative and executive powers.[23] Customary law, as the name suggests, is arbitration held in accordance with customary law and usage and a method of resolving disputes and claims among members of the various communities in Ghana. This is an old practice and before the advent of colonial rule. This is recognized by Article 11(2) of the Constitution, 1992[24] and is a unique feature of Act 798.Chieftaincy is one of the resilient institutions that have withstood all the phases of the country’s socio-political history; during pre-colonial, colonial and post-colonial eras. The 1957 and 1960 Constitutions guaranteed the institution of chieftaincy, the relationship between the central government and the chiefs were frosty with the passing of Act 81 which defined chiefs to include recognition by the Minister responsible for local government. [25] In fact, the Act gave powers to the ruling political party to interfere in chieftaincy issues. The 1969, 1979 and 1992 Constitutions affirm the relevance of the chieftaincy institution and frown on governmental and legislative meddling in chieftaincy matters.

According to Owusu-Mensah (2014), the chieftaincy institution is considered as the bond between the dead, the living and the unborn that occupies the vacuum created, by the modern partisan political structures, in terms of customary arbitration and the enforcement of laws at the communal level.

The 1992 Constitution/Chieftaincy Act 2008

Due to its sanctity, relevance and the unique values, the framers of the 1992 Constitution devoted Articles 270 to 277 to Chieftaincy and together with the Chieftaincy Act, 2008 (Act 759) provides the qualifications for chiefs in Ghana and these include hailing from the appropriate family and lineage, validly nominated, elected or selected and enstooled, enskinned or installed, and must be a person who has not been convicted of high treason, treason and high crime or offence relating to the security of the state, fraud, dishonesty or moral turpitude. Act 759 which provides under section 30 for customary arbitration, states that “the power of a chief to act as an arbitrator in customary arbitration in any dispute where the parties consent to the arbitration is guaranteed.” T[26]his meaning that all traditional authorities are deemed as customary arbitrators.

The case like BUDU II V CAESAR[27] and others spell out the basic ingredients or essential characteristics of a valid customary arbitration.

Chiefs Involvement in the Management of State

Although the 1992 Constitution per Article 276 barres chiefs from taking part part in “active party politics with emphasis that chiefs wishing to partake in active party politics shall abdicate their stool or skin, the Constitution provides for the involvement of chiefs in the management of the state and resources[28]. For instance, Article 89(2(b) states that the President of the National House of Chiefs (NHCs) shall become a member of the Council of State.[29] Article 153(m), [30]provides for the representation of the NHCs on the Judicial Council, Article 255(1)(c) provides for representation of the Regional House of Chiefs (RHCs) on the Regional Coordinating Councils[31], Article 259(b)(i) provides for representation of the NHCs on the Lands Commission while Article 261(b)(i) provides for the representation of the RHCs on the Regional Land Commision.[32]

By the Constitution, 1992, legislations and conventions, chiefs are appointed to serve on state and statutory boards and commissions. The National Aids Commission, Ghana National Petroleum Corporation, Forestry and Land Commissions, Ghana Cocoa Board, National Museums and Monuments Boards, boards of financial institutions, among others are typical examples.

Prominent chiefs such as Nana Professor S. K.B. Asante, Paramount Chief of Asokore, Asante, Nana Effah-Apenteng, Bompatahene, former Ambassador and Permanent Representative, Permanent Mission of Ghana to the United Nations, New York, Chief of Staff of the Eminent African Personalities established by the African Union to Mediate the 2007/2008 Kenya Post-Election Crisis and Chairman of KNUST Governing Council, Professor John S. Nabila, Wulugu Naba; former President of the NHCs and the chairman of the National Population Council, Head, Department of Geography and Resource Development, Oseadeeyoo Akumfi Ameyaw; Techimanhene, a member of the Council of State, lawyer, agriculturist, former banker and member of the National Peace Council, Prof. Nana Kobina Nketsia V, Esikadomanhen, Professor of African History, former lecturer at the University of Cape Coast, Chair for the Advisory Board of WaterAid, Ghana, Deputy Chair of Bisa Abrewa Museum, and a Director of the Panafest (Pan African Festival) Foundation, international speaker and author, Awulae Attibrukusu III; Paramount Chief of Lower Axim, University graduate and agricultural extension officer, former Vice President, NHCs, former member, Ghana National Petroleum Corporation and Board Member, Assemblies of God University Council. He is copiously quoted in Ghanaians land law cases. Oseadeayo Agyemang Badu II; Dormaahene and Judge, Togbe Afede XIV; the Agbogbomefia of the Asogli State, former President of the National House of Chiefs, Executive Chairman of World Trade Centre Accra and co-founded Sunon Asogli Power Ghana Ltd, Databank Financial Services and Africa World Airlines Ltd.[33] are just a few of Ghanaian traditional leaders with the requisite standing, qualifications, fortitude and moral turpitude to serve on boards including the ADR Centre Board.

Ghana Arbitration Centre

Nana Professor S. K. B. Asante, Paramount Chief of Asokore, Asante, was instrumental in the establishment of Ghana Arbitration Centre. He was an International Arbitrator and served on the International Court of Arbitration of the International Chamber of Commerce, International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), Paris and a Co-Founder and Chairman of the Ghana Arbitration Centre and founding President on the Institute of International Negotiations.

Yendi Crisis Resolution

The Eminent Chiefs, comprising the Asantehene, Otumfuo Osei Tutu II as the Chairman together with the Overlord of Mamprugu, Nayiri Naa Bohagu Abdulai Mahami Sheriga and Yagbonwura, Tuntumba Boresa I, played critical role in resolving the Dagbon crisis, bringing peace and the final installation of the Ya-Naa in November 2018,[34] a conflict which was restarted in 2002.

Less than half of a loaf

A critical look at section 115(2) (j) and (k) of Act 798 state inter alia that the ADR Board/Centre shall (j)register experienced or qualified persons who wish to serve as customary arbitrators and keep a register of customary arbitrators[35]; and (k) request the traditional councils to register and keep a register of persons who wish to serve as customary arbitrators. This, particularly, subsection 2(k) of the Act admittedly appears to acknowledge the roles and contribution of chiefs and traditional councils in customary arbitration and seeking to give the noble institution of chieftaincy a role to register and keep register of persons who wish to serve as customary arbitrators and not as Board members. There is obviously a gap or an omission. It is less than half of a loaf.

Observations/Conclusions

From the scrutiny of the the historical developments, the provisions of the 1992 Constitution and the ADR Act 2010, case studies, official actions, among others, the contribution of traditional rulers to the growth and prioritizing ADR is phenomenal. However, they are expressly or explicitly excluded from the membership of the Board of ADR, for now the governing authority in ADR practice in Ghana.

However, section 115(2)(k) which states that the ADR Board/Centre shall request the traditional councils to register and keep a register of persons who wish to serve as customary arbitrators seems to acknow[36]ledges the monumental roles and contribution of chiefs and traditional councils in customary arbitration and offers some minimal role to the chiefs/traditional councils to work on customary arbitration.

Recommendations

In order to fully bring traditional rulers and chiefs in the mainstream administration or ADR governance in Ghana, the author proposes the following measures:

- Amendment of the ADR Act 2010 (Act 798)

An amendment of the Act 798 in relation with the composition of the ADR Centre Board to include representatives of chiefs or traditional councils may be a cure to the omission or exclusion of traditional rulers from the ADR Centre Board. The State may do this even if it is a paragraph proposal to amend the Act. A member of parliament in this age of private member sponsorship of legislations and motions for amendment may not be out of place. It is an opportunity to showcase the uniqueness and values of our chiefs and ADR to the world once again.

- Promulgation of a legislative instrument

Having already identified some gaps and omissions in the current ADR (Act 798) such as the exclusion of negotiation as one of the ADR mechanisms in the Act (no provision in the Act on ADR), the exclusion of traditional rulers from the ADR Centre Board, and others, passing a subsidiary legislation to close the gaps may also be another alternative towards strengthening the ADR Act 2010 and ADR practice in Ghana. Once Ghana signals this, Nigeria, Togo, South Africa and other countries where traditional governance is strong may emulate Ghana.

Alternatively, in appointing members of the ADR Board, the appointing authority must be intentional and deliberate to include a chief or representative of the National House of Chiefs. This may be developed to become a convention if we do not intend to amend the current ADR Act to include chiefs on the ADR Centre Board.

4.Proactive role of chiefs in deepening ADR practice

Chiefs/traditional leaders have the capacity to contribute more to the development of ADR in Ghana and beyond. With the background in arbitration and customary law and practice, chief can proactively promote customary arbitration and ADR in general in the communities by setting up ADR centres and encouraging participation by the citizens.

Bibliography

Constitutional provisions

Article 11(2) of the 1992 Constitution of Ghana

Article 89(2b) of the 1992 Constitution of Ghana

Article 153(m) of the 1992 Constitution of Ghana

Article 233 (b) of the 1992 Constitution of Ghana

Article 256 (b)(1) and Article 261(b) of the 1992 Constitution of Ghana

Articles 270 – 277 of the 1992 Constitution of Ghana

Article 276 of the 1992 Constitution of Ghana

Legislative provisions

Alternative Dispute Resolution Act, 2010 (Act 798), sections:

section 114 of the Act 798

section 115 of the Act 798

section 115(2)(j) of Act 798

section 115(2)(k) of Act 798

Section 117 of Act 798

Section 117(1) (a) of Act 798

section 117(3) of Act 798

section 30 of the Chieftaincy Act, 2008 (Act 759)

Section 190(3) of the Companies Act, 2019 (Act 992)

Cases

BUDU II v. CAESAR & ORS. [1959] GLR 410- OLLENNU J. Land 4

Okudzeto and Others vs. Irani Brother and Other (NO. 2) [1973]DLHC2305 and Commodore v Fruit Supply Ghana Ltd [1977] GLR, 241, CA.

Journals/articles

Ahmed Ibrahim, Transforming Dagon chieftaincy conflict in Ghana: perception on the use of Alternative Dispute Resolution, doctoral dissertation, Nova Southeastern University, htpps://nsuworks.nova.edu/shss, 2018 (accessed on 20th July 2024).

Amegatcher Nene A. O., “A Daniel Come To Judgement: Ghana’s ADR Act, a progressive or retrogressive piece of legislation?” September 2011.

Amoasi Christopher, ‘Advancing Civil Justice Reform and Conflict Resolution in Africa and Asia: Comparative Analyses and Case Studies,’ 2021 (accessed on 26th July 2024).

Bella Djibril Faisal Esq & Pharm, Associate Partner, Akpalu, Yartey & Associates, Barristers and Solicitors, Accra.

Brakopwers Kwabena A, An Evaluation of Ghana’s Alternative Dispute Resolution Act, 2010, (Act 798), Thirteen Years on. Available at https: SSRN://ssrn.com, 2023.

Elachi Agada J., African Lawyers and Alternative Dispute Resolution, https://www.plagscan.com/highlight (accessed 20th August 2024).

Frempong, A.K. D. Chieftaincy, Democracy and Human Rights in Pre-Colonial Africa: The Case of the Akan System in Ghana Chieftaincy in Ghana: Culture, Governance and Development. Ed. Irene K. Odotei and Albert K. Awedoba (Accra: Sub-Sahara Publishers, 2006)

Historical Developments of the Courts before Independence- The Supreme Court Ordinance, 1876 (www.judicial.gov.Ghana/history/before-Indy/page.2. Accessed on August 1, 2024.

Hon. Torgbor, Edward, “Ghana’s Recently enacted Alternative Dispute Resolution Act 2010 (Act 798): A Brief Appraisal,’ 2011.

https://www.africanlawbusiness.com/news/6067-alternative-dispute-resolution-in-kenya (accessed 21st August 2024).

https://www.nhoc.gov.gh (accessed 26th August 2024

Naa Dei Kotey Audrey & Alesu-Dordzi S., ‘Recent Developments in Arbitration in Ghana’, https://globalarbitrationreview.com/review/the-middle-eastern-and-african-review/2022 (accessed 14th August 2024).

Nartey Alex & Owusu-Koranteng Daniel, interview, 8th August 2024.

Nwauche E. S, quoted Paul Kurgis in the article, ‘State Responses to Outcomes of Traditional Justice Resolution Mechanisms in Commonwealth Africa: customary Aribitration in Nigeria and Ghana,’ 4 Journal of Commonwealth Law 43 (2022).

Onyema Emilia, ‘The New Ghana ADR Act 2010: a critical overview,’ Arbitration International, vol. 28. Issue 1, 2012.

Owusu-Mensah Isaac, ‘Politics, Chieftaincy and Customary Law in Ghana’s Fourth Republic, the Journal of Pan African Studies, Vo. 6, no. 7, February 2014.

Parliamentary debates (official report/hansard) 7.2, 9th December 2009.

Taha Mohammed O., http://www/loc.gov/law/help/arbitration/egypt (accessed 21st August 2024).

About the Author

Kojo Kwarteng is a journalist, professionalpublic relations practitioner, marketer, media management and communications expert, author and holds Diploma in Journalism, BSC in Business Administration, MBA Marketing, LLB, Executive Business Education, LLM and Executive Masters in ADR from the Ghana Institute of Journalism, University of Ghana Business School, Central University, Mountcrest University College, Northwestern University, Illinois, USA, University of Essex, UK and IPLS and an intern of Akpalu, Yartey & Associates Law Firm, Accra.

Email: kojokwarteng2032@gmail.com/kwarteng30@yahoo.co.uk

Telephone: 233 243268036

[1] Naa Dei Kotey Audrey & Alesu-Dordzi S., ‘Recent Developments in Arbitration in Ghana’, https://globalarbitrationreview.com/review/the-middle-eastern-and-african-review/2022 (accessed 14th August 2024).

[2] Nwauche E. S, quoted Paul Kurgis in the article, ‘State Responses to Outcomes of Traditional Justice Resolution Mechanisms in Commonwealth Africa: Customary Aribitration in Nigeria and Ghana,’ 4 Journal of Commonwealth Law 43 (2022).

[3] Owusu-Mensah Isaac, ‘Politics, Chieftaincy and Customary Law in Ghana’s Fourth Republic, the Journal of Pan African Studies, Vo. 6, no. 7, February 2014.

[4] Amegatcher Nene A. O., “A Daniel Come To Judgement: Ghana’s ADR Act, a progressive or retrogressive piece of legislation?” September 2011.

[5] Torgbor, Edward, “Ghana’s Recently enacted Alternative Dispute Resolution Act 2010 (Act 798): A Brief Appraisal.”

[6] Onyema Emilia, ‘The New Ghana ADR Act 2010: a critical overview’ ArbitrationInternational, vol. 28. Issue 1, 2012.

[7] Frempong

[8] https://www.ibanet.org/the-nigerian-arbitration-and-mediation-act-2023 (accessed 7th September 2024).

[9]Elachi Agada J., African Lawyers and Alternative Dispute Resolution, https://www.plagscan.com/highlight (accessed 20th August 2024).

[10] Taha Mohammed O., http://www/loc.gov/law/help/arbitration/egypt (accessed 21st August 2024).

[11] https://www.africanlawbusiness.com/news/6067-alternative-dispute-resolution-in-kenya (accessed 21st August 2024).

[12] Section 117 of the ADR Act 2010 (Act 798)

[13] Section 117 (1) (a) of the Act 798

[14] Nartey Alex & Owusu-Koranteng Daniel, interview, 8th August 2024.

[15] section 117 (3) of Act 798

[16] section 114 of the Act 798

[17] section 115 of the Act 798

[18] Official publication of parliamentary debate (Hansard), 24th March 2010.

[19] Graphiconline.com, July 17, 2024.

[20] Official publication of parliamentary debate (Hansard), 7.2, 9th December 2009.

[21] Section 190(3) of Companies Act, 2019 (Act 992) and Okudzeto and Others vs. Irani Brother and Other (NO. 2) [1973]DLHC2305 and Commodore v Fruit Supply Ghana Ltd [1977] GLR, 241, CA.

[22] . Amegatcher Nene A. O, “A Daniel Come To Judgement: Ghana’s ADR Act, a progressive or retrogressive piece of legislation?” September 2011

[23] Owusu-Mensah Isaac, ‘Politics, Chieftaincy and Customary Law in Ghana’s Fourth Republic, the Journal of Pan African Studies, Vo. 6, no. 7, February 2014.

[24] Article 11(2) of the 1992 Constitution of Ghana.

[25] Chieftaincy Act 1961, Act 81 (Accra Assembly Press, 1961 now Ghana Publishing Company Limited).

[26] Section 30 of the Chieftaincy Act, 2008 (Act 759).

[27] BUDU II V CAESAR & ORS. [1959] GLR 410- Ollennu J. Land 4

[28] Article 276 of the 1992 Constitution of Ghana

[29] Article 89(2(b) of the 1992 Constitution of Ghana

[30] Article 153(m) of the 1992 Constitution of Ghana

[31] Article 255(1)(c) of the 1992 Constitution of Ghana

[32] Article 259 (b)(i) and Article 261(b)(i) of the 1992 Constitution of Ghana.

[33] https://www.nhoc.gov.gh (accessed 26th August 2024).

[34] Ahmed Ibrahim, Transforming Dagon chieftaincy conflict in Ghana: perception on the use of Alternative Dispute Resolution, doctoral dissertation, Nova Southeastern University, htpps://nsuworks.nova.edu/shss, 2018 (Accessed 29th July 2024).

[35] section 115(2)(j) of Act 798

[36] section 115(2)(k) of Act 798