This is the 2nd Piece of a 4 part series. Part 1 may be obtained here.

Cascading Effect

Such factors not only affect the accused individual’s right to a fair trial within a reasonable timeframe but also impact other parties, such as witnesses. When a witness for the prosecution is present in court but the prosecution is unable to produce the accused or the case does not proceed due to the need for amendments, both the case and the witness experience an adjournment.

Although sections 65 and 66 of the Courts Act, 1993 (Act 459) allow the court to order that a witness be compensated from the Consolidated Fund to cover their reasonable expenses and provide reasonable remuneration for their loss of time and inconvenience, the process of obtaining such funds is so cumbersome that witnesses often forgo pursuing it.

They ultimately incur their own expenses when attending court. The time spent in court also impacts various aspects of a witness’s life, including professional and familial obligations, as it involves not only time but also additional challenges. Thus, some witnesses are unlikely to willingly return to court after an adjournment, and this may in turn occasion further adjournments, as the prosecution may seek adjournments to try to convince them to appear in court to testify.

Overall, there is a cascading effect on all participants when one component of the criminal justice administration falters.

Judges frequently endeavor to balance the fundamental rights of an accused individual to a fair trial within a reasonable timeframe while simultaneously addressing the unique challenges faced by the prosecution.

In pursuit of this balance, courts may adjourn cases for periods shorter than fourteen days and mandate the prosecution to produce the accused. In extreme circumstances, they may issue a summons to the station officer, divisional commander, or crime officer to appear in court and show cause for their failure to produce the accused. Often, after such summons are issued, the accused is promptly presented in court on subsequent adjournments, often at the expense of other accused persons standing trial before other courts.

“The Docket has been Forwarded to the Attorney General for Advice.”

One rationale for the Attorney General’s delegation of prosecutorial powers in summary cases to the police is to ensure the expeditious conduct of such trials. However, whenever the prosecution seeks the Attorney General’s advice in pending cases, there is often an inordinate delay. According to the prosecution, this delay is attributed to the bottlenecks encountered in forwarding dockets to the Attorney General’s office, even within the same region, as well as the challenges an attorney faces when requesting additional evidence or information necessary to provide informed advice. It is not uncommon for the Attorney General’s advice to remain pending for over three years.

In such instances, the prosecution’s submission to the court on all dates is that the docket has been forwarded to the Attorney General’s Office for advice. Given that the Attorney General is a party to a case, similar to an accused individual, the courts are unable to accommodate police prosecutors during such prolonged delays, often resulting in the dismissal of the case and a discharge of the accused person.

I have previously mentioned the potential for the police to re-arrest a discharged individual and restart the legal process. While this practice is legal, it appears to be unjust to the accused and tarnishes Ghana’s international reputation regarding adherence to fair trial principles and the fundamental human rights of the accused, particularly the presumption of innocence, it also appears to incur substantial costs and time for the state in prosecuting a single crime.

Practice vs. Theory

Before concluding the discussion on the challenges faced by prosecutors, it does appear that the unique difficulties stemming from limited funding and the lack of a coordinated system are undermining the overarching objective of the Practice Directions on Disclosures and Case Scheduling, which aim to ensure that trials are conducted fairly and within a reasonable timeframe.

This is evidenced by the scarcity of instances, if any, where the prosecution has been able to file its disclosures and witness statements immediately following the entry of a not guilty plea by the accused. It has become increasingly common for prosecutors to require a minimum of three adjournments, each comprising thirty clear days when the accused is on bail, and approximately five adjournments of fourteen clear days when the accused is remanded pending trial, to file disclosures and witness statements.

The reasons for these delays include inadequate facilities for typing and printing documents, the non-cooperation of witnesses in signing statements, and the unavailability of investigators or crime officers who possess essential documents that must be disclosed. Both police prosecutors and attorneys from the Attorney General’s Department have occasionally submitted to the court that they have personally financed the typing and printing of documents, as well as the expenses incurred in transporting witnesses to sign their statements. Consequently, even after the prosecution has made disclosures and the case management conference has concluded with the court and parties setting definitive trial dates, it is premature to express optimism. This caution arises from the fact that, as previously noted, the absence of an accused person in lawful custody complicates the court’s ability to proceed expeditiously with the trial.

Additionally, the further absence of a prosecutor and witnesses, who, due to the complex nature of compensation, appear to receive no remuneration from the legal system for their involvement, exacerbates the delays. Furthermore, the absence of lawyers for the accused, which will be discussed in greater detail in subsequent paragraphs, also significantly contributes to delays in criminal proceedings.

1.1 EFFORTS AT RESOLUTION

Case Tracking System

To address this issue, a few years ago, USAID funded a justice sector project that connected the courts, the Attorney General’s Department, various police stations under the courts’ jurisdiction, and prisons, known as the Case Tracking System. Its aim was to enhance coordination among the various actors in the justice sector and improve information sharing to promote efficiency and effectiveness in the administration of criminal justice. However, there is a significant lack of data regarding the project’s effectiveness.

Virtual Courts

The Judiciary has implemented virtual courts in several regions to expedite hearings. Virtual courts could potentially serve as a solution to the issue of undue delays in criminal trials if measures are taken to ensure that all relevant stakeholders are included.

Tying All Ends

It is insufficient for the court to have a stable and reliable internet connection if the prosecution and the accused lack access to a reliable connection and electronic devices such as laptops. For the system to be effective and efficient, basic facilities such as internet connectivity must be established across all police stations, Attorney General’s offices, and prisons. They must also have access to essential electronic equipment, such as laptops or desktop computers, specifically designated for the purpose of participating in virtual hearings.

When an accused individual has met the terms of their bail, it is reasonable to expect them and their counsel to bear the costs of their own internet connectivity. However, when an accused individual is in custody, the state must bear the responsibility of providing internet access and other necessary facilities (Article 19 (2) (e)) to enable full participation in proceedings and adequate preparation for defense. Similarly, prosecutors should be provided with essential resources, such as internet connectivity, to prevent situations where they must incur personal expenses.

A robust and stable internet connection allows prosecutors to remain in their offices or other convenient locations, while the accused can be at home, in prison, or at a police station, with their counsel also able to join court proceedings from their offices. For prosecution witnesses, the Attorney General may consider providing them with data in advance, assuming they have access to smartphones or other relevant electronic devices and stable internet connectivity in their locations, or have them join proceedings from the Attorney General’s office.

Possible Challenges

A challenge that may arise concerns witnesses for the accused, specifically regarding who will bear the costs of providing them with data and access to electronic devices, particularly when the accused individual is in custody. One could argue that since the state is responsible for detaining the accused individual, data could be classified as “adequate facilities” under the constitutional provision in Article 19(2)(e), and thus the state must provide this to the witnesses of the accused to facilitate the accused’s ability to mount a defense. I acknowledge that even if the argument is valid and the state is required to provide such data, the issue of which state agency will be responsible, be it legal aid, the Attorney General’s office, or the police through the investigator, must be addressed. Subsequently, the persistent issue of inadequate funding for these agencies will also need to be considered.

For the time being, while we collectively seek a solution, it may be reasonable to request that witnesses for the defense appear in person wherever the court sits virtually, i.e., the courtroom or the judge’s chambers, so that their testimony can be recorded while all parties participate virtually.

All is Not Well…

Additional issues, such as the submission of original documents and materials, the rights of the accused or their counsel to examine such materials and raise necessary objections, and access to pertinent exhibits during cross-examination, can all be addressed on a case-by-case basis rather than through a one-size-fits-all approach as they arise during the trial. For instance, in a trial concerning the possession and trafficking of narcotic substances, it is the right of the defense counsel to insist on the physical production and inspection of all narcotic substances prior to their submission as evidence. In such instances, it may be agreed between the court and all parties that the witness intending to submit this evidence should be the last witness called and that this testimony should occur in open court rather than virtually. Once a date is established for the appearance of this witness and all parties, necessary arrangements can be made in advance to ensure the trial proceeds on that date.

Evaluating Evidence: The Demeanor of a Witness

I concede that there are valid concerns regarding the challenges faced by the court and parties concerning the demeanor of witnesses who testify virtually. This concern is justified, as the credibility of a witness significantly influences the weight a court assigns to their testimony, with demeanor being a critical determinant of credibility. Even in virtual proceedings, provided that internet connectivity is stable, the court and parties can observe and evaluate the demeanor of a witness, assuming the court remains vigilant and attentive. However, I contend that demeanor is not the sole means of assessing credibility During the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, all parties involved in a case, including the court, were masked, rendering the faces of witnesses largely obscured. Nonetheless, courts were still able to assess the credibility of witnesses.

Virtual hearings should be regarded as an innovative and cost-effective approach to alleviating case backlogs in the courts, significantly expediting trials, and reducing or eliminating unnecessary delays. For this approach to succeed, extensive efforts should be made to engage all stakeholders and secure their support.

1.2 A Concerted Effort

It may be necessary to make a concerted effort not only to advance laws and policies on paper but also to provide the tools and training essential for their effective implementation in practice. Only through a combination of both can we ensure the achievement of the desired objective of expediting trials and satisfying the expectations of Ghanaians for timely justice. Without such a collective effort, we risk perpetuating a cycle in our attempts to enhance the efficiency of the justice system. We may resolve one issue only to discover that the solution has created another. For example, while the introduction of witness statements aims to eliminate surprises during trials and has removed the manual recording of evidence in chief, insufficient training and resources for prosecutors have resulted in trial delays.

Previously, trials could commence immediately after a plea of not guilty was entered, provided at least one witness for the prosecution is present in court; now, several adjournments are often necessary for the filing of disclosures. Additionally, real-time transcription of evidence is now available in nearly all courts due to automation, alleviating the problem of frequent adjournments for typing and compiling proceedings. This advancement has also mitigated the health issues associated with manual recording by judges and will reduce the judiciary’s expenditure on procuring record books and pens.

Also, as screens are accessible to both the bar and the bench, any errors in the proceedings can be corrected instantaneously, thereby eliminating the need for judges to supervise typed proceedings and also ensuring that proceedings are accurately captured. However, it appears that many court recorders require further training to improve their typing speed or the judiciary needs to invest in speech-to-text apps, as trials have become lengthier due to frequent breaks between questions and answers to ensure that recorders can capture all spoken content. Evidently, in addressing one problem, we seem to have introduced another. I believe that with the appropriate orientation and a collective effort, we can deliberate on some of the potential challenges posed by new regulations and work toward resolving them. After implementation, there must be a sustained effort to continuously assess challenges and identify methods for mitigation. Simply enacting new laws and policies without adequate provisions for addressing initial problems will lead to a perpetual cycle of inefficiency.

2.0 MISSING DOCKETS: ADDRESSING SYSTEMIC FAILURES

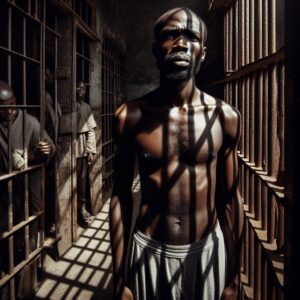

This discourse would be incomplete without addressing the critical issue of missing criminal dockets in court cases. Reports frequently indicate that individuals on remand have been detained for prolonged periods due to the absence of their dockets from court records. When dockets are reported missing, the perception arises that illicit activities may have occurred. While this assumption may occasionally hold true, it is not universally applicable. I will elaborate on this matter.

Upon filing a criminal case, it is assigned a suit number and placed within a designated jacket, referred to as the docket.

All subsequent filings related to that case are included in the docket. Once a final judgment is rendered, the docket is considered closed unless an appeal is filed, in which case the entire docket must be transmitted from the trial court to the appellate court. Throughout the docket’s lifecycle in the trial court, following an adjournment by the judge, the next court date is recorded in the court’s diary. Entries are made in the docket, and the adjourned date is noted on the docket’s front page.

Additionally, a summary of proceedings is documented in the Things Book. Some courts utilize laptops to record the adjournments of all cases scheduled for a given day. After these procedures, court clerks return the docket to the docket clerk. The docket clerk is responsible for organizing dockets by adjournment dates, verifying this information against the cause list, and ensuring that dockets are delivered to the court before the commencement of daily proceedings. Except in cases that are adjourned sine die, struck out for want of prosecution, or intended to proceed normally, there must always be a return date. A court clerk who lacks diligence or is overwhelmed may neglect to follow up with other clerks regarding the absence of an adjourned date on a particular docket.

The disappearance of a court docket typically occurs during its transit between the courtroom and the docket clerk. Missing dockets can arise in two primary ways.

Firstly, if the adjournment date is not recorded in the court diary and on the docket, a court clerk may lack awareness of the adjourned date unless they consult the Things Book or the electronic record on the laptop. If diligence is lacking, the docket may be left unattended, leading to its potential misplacement among other dockets or being forgotten altogether. Secondly, a rogue courtroom clerk, compromised by a party involved in a case, may intentionally neglect to return a docket to the docket clerk. Conversely, if the docket clerk is also compromised, they may conveniently fail to return it to the court on the specified return date. If the individual responsible for composing the cause list is complicit, the case may not be included in the weekly cause list.

Given the extensive caseloads judges manage, if a pending matter is not reflected on the cause list, it is improbable that the judge will recall it. Some judges may eventually inquire about the absence of a particular case from court for an extended period, at which point they may discover the docket’s absence. To mitigate the issue of missing dockets, some judges make it a practice to announce prior to adjournment that any individual present in the courtroom should notify the court if their case has not been mentioned.

However, even with such measures, if the missing docket involves corrupt elements, including prosecutors, investigators, and court staff, it is likely that an accused individual will not be presented in court from custody on the return date, inhibiting their ability to alert the court that their case remains unaddressed. Consequently, when an accused person lacks legal representation or family members present in court, the origins of the missing docket become evident.

2.1 Reconstructing Missing Dockets

It is important to acknowledge that missing dockets can be reconstructed if the issue is promptly brought to the court’s attention. Utilizing the court’s diary, record book, and Things Book, all relevant proceedings can be transcribed onto a new docket. Copies of charge sheets and other filed processes can be obtained from the prosecution, as well as from the accused individual and/or their counsel.

The public’s outcry regarding missing dockets is justified, as citizens have a right to expect diligence and security from the courts. However, given that the judiciary is a human institution, the potential for human error or corrupt practices resulting in missing dockets cannot be entirely eradicated.

When an accused individual in prison custody faces the issue of missing dockets, it is crucial for them to notify the prison director immediately. The prison director should verify the warrant of the accused, which typically includes a return date and the name of the court where the trial is pending.

Additionally, prison records will contain the name of the investigator who delivered the accused to the facility and their associated station. Even if the return date has long passed, the accused individual must be returned to the investigator, who will promptly inform their superior.

If the investigator or police station cannot be located, the prison director must ensure the accused is presented to the court registrar, who will inform the judge.

In cases where the accused is in police custody, the station officer or commander must immediately contact the investigator and prosecutor to address the delay in the accused’s release. The court registrar must be notified promptly, and they, in turn, must inform the judge to facilitate the reconstruction of the docket. A prison director or police commander who continues to detain an accused individual after the warrant has expired is in violation of the law, as custodians may only retain individuals who are legally authorized to be in custody under a court warrant, as outlined in the Prisons and Police Service Act.

Whenever missing dockets are reported to the court, it is essential not only to ensure their swift reconstruction but also for the judge to initiate an investigation and notify the Judicial Secretary or the Supervising High Court Judge.

H/HBertha Aniagyei*