Ghana’s Interior Minister, Alhaji Muntaka Mubarak and Foreign Minister, Okudzeto Ablakwa, in separate public engagements have announced plans to deport foreigners arrested on suspicion of committing illegal mining (galamsey) or defrauding by false pretences, particularly through cybercrime.

Alhaji Muntaka Mubarak, Minister for the Interior, on his part addressing stakeholders in the Zongo communities as part of his visit to the Ashanti region, is reported to have said:

“Galamsey stands as one of Ghana’s most pressing challenges. It has come to our attention that certain foreign nationals, particularly those from China, are actively participating in these unlawful activities. Our position is unequivocal – once apprehended, they will be deported. In the event that we apprehend any foreign national partaking in this illegality, we will not hesitate to repatriate them to their home country”.

Mr Okudzeto Ablakwa is reported to have said that deportations are already underway stating that: “Already, a lot of deportations have been carried out. We’ve just not been advertising them”

Understandably, these pronouncements have ignited significant alarm within the foreign community, given the devastating consequences of forced removals. Beyond the immediate trauma, such actions risk tearing apart families, crippling established businesses, and fundamentally destabilizing the lives and livelihoods of entire communities. Locally, skepticism regarding the efficacy of these deportations is also rife, starkly illustrated by the widely publicized case of Aisha Huang, whose prior deportation proved to be no barrier to her subsequent re-entry.

The question that arises is whether these deportations are lawful and accordance with due process.

Any assessment of the lawfulness and procedural fairness of these deportation plans must be firmly rooted in Ghana’s Immigration Act 2000 (Act 573). This foundational legislation re-establishes and updates the legal framework concerning all aspects of immigration, including the critical issue of the removal of foreign nationals.

Section 35(1) provides that (1) A foreign national is liable to deportation if—

(a) a court recommendation for his deportation is effective under subsection (2) of this section;

(b) he has been found by a court to be destitute or without means of support or to be of unsound mind or mentally handicapped;

(c) he is a prohibited immigrant;

(d) he is in Ghana without a valid permit, or any of the conditions on which his permit was granted has been broken; or

(e) his presence in Ghana is in the opinion of the Minister not conducive to the public good.

So a foreign national may be “liable” i.e. lawfully subjected to deportation -by an effective court recommendation under Section 35(2) which will be looked at in more detail, by a specific court finding of fact as to destitution and mental sanity, by falling within the criteria provided in the law as qualifying as a “prohibited immigrant”[1] ,by being in Ghana without a valid permit or that the conditions of a valid permit has been broken or whenever the Minister of Interior takes the view that the foreigner’s presence in Ghana is not conducive to the public good.

Sections 35(2) and (3) add that:

35(2) A recommendation for deportation is effective if it is made by a court upon conviction for an offence punishable by a term of imprisonment exceeding three months with or without a fine and

(a) on an appeal against the conviction, the appellate court has upheld the recommendation; or

(b) no appeal has been brought within the time allowed for appeal but the recommendation was made by—

(i) the High Court, or

(ii) an inferior court and has been approved by the Chief Justice.

35(3) Where a court makes a finding under paragraph (b) of subsection (1), the court shall report the finding in writing to the Minister.

Essentially, the statute puts in place safeguards to ensure that a court cannot just make a unilateral recommendation to deport a foreign national. For the order to be effective, the foreign national must have been convicted for an offence punishable by a term of imprisonment exceeding 3 months – the implication therefore being that the prosecution would have proven guilt beyond a reasonable doubt after a full trial wherein the foreigner was fully heard in his defence or that the said foreigner pleaded guilty outright

The foreign national’s rights of appeal are preserved: the conviction giving rise to the recommendation may be challenged and overturned, thereby automatically nullifying the deportation recommendation. Even if the conviction is affirmed, the deportation recommendation only stands if the appellate court expressly upholds it. Where no appeal is filed within the statutory period, the recommendation becomes effective if it was made by a High Court or an inferior – I quite prefer the expression “lower” court, (with the Chief Justice’s approval). Finally, if the court finds the foreign national destitute or mentally incapacitated, it must report the matter to the Interior Minister.”

Dr. Richmond Osei-Hwere J had the opportunity to make a judicial pronouncement on these provisions in The Republic v. Ravi Kaushik & Vishu Bawa at large (F23/15/21) delivered on 11 Feb 2022, an appeal from a lower court – District Court, Prestea. There the accused person had pleaded guilty to stealing and causing unlawful harm and the trial judge made recommendations for their deportation based on representations made by the Police Service to the effect that they had no “work permit”, “no visa” and “their resident permit had also expired”. Osei-Hwere J overturned the deportation recommendation and substituted same for a fine on two grounds:

- The representations made by the police were not in evidence and there were therefore simply unsubstantiated claims. The appellants had no opportunity to be heard on same and this breached the foundational rule of audi alterem partem.

- Crucially the order had to go through the Chief Justice to be effective and having failed to do it the court had acted unlawfully.

The Court delivered itself as follows:

“One may wonder how the court could decide on the immigration status of the Appellant without hearing the matter. It was wrong for the court to rely on the said findings of police investigations since same was not in evidence. The case never went through a full trial for the Appellant to respond to the said findings by the police which for all intents and purposes were mere allegations.”

“….By section 35 (2) (b) (ii), the recommendation for deportation must be directed to the Chief Justice. It is only the Chief Justice who can give a stamp of approval or otherwise to a recommendation for deportation. The court fell into serious error when it recommended the Appellant’s deportation to the Ghana Immigration Service without passing through the Chief Justice for approval.

The decision suggests that a guilty plea to a qualifying offence satisfies the conviction requirement under Section 35(2). To simplify, in the scenario where a foreigner pleads guilty thereby forestalling a full trial, that plea may ground a qualifying conviction.

A court only needs to conduct a separate inquiry into immigration status if it intends to rely on extraneous allegations (e.g., police claims about expired permits) as the basis for a deportation recommendation. Where the court makes reliance on these additional factual claims (e.g., “no work permit”), those claims must be proved through evidence, and subject to the defendant’s right to respond (audi alterem partem).

The decision also affirms the law that lower courts cannot bypass the Chief Justice’s scrutiny, reinforcing hierarchical oversight.

Section 36—Deportation Order.

(1) The Minister may by executive instrument order the deportation of any person liable to deportation.

(2) The order may be made subject to such conditions as the Minister may impose.

(3) A deportation order may include the dependants of the person to be deported if the Minister so directs.

As discussed earlier, persons are liable to deportation where the Minister takes the view that their presence in Ghana is not conducive to the public good. The law provides that the this executive function of deportation is carried out by the Minister by means of an Executive Instrument. The deportation order may be subject to conditions and may include the deportation of persons who rely on the said foreign national for support if the Minister directs so.

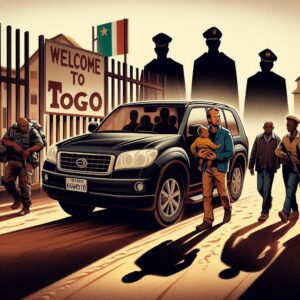

The broad nature of the discretionary power provided in the statute appears to lend itself to abuse, and was the subject matter of litigation in Republic v. Minister For The Interior; Ex Parte Bombelli (1981) delivered on 9 Jan 1981 by the fearless jurist Cecilia Koranteng-Addow J (one of the 3 High Court Judges abducted and murdered on June 30, 1982). The facts make for interesting reading. The applicant was an Italian investor named Enzo Bombelli who dealt in general equipment and hunting cartridges, was arrested and informed that a deportation order was made against him. He was eventually escorted with his son across the Aflao border into Togo and warned never to come back. According to the applicant, he read in a copy of the Daily Graphic he obtained at Lome about a press conference which was held by the Minister of Interior, Ekow Daniels in Accra. At the press conference the minister is alleged to have given the reasons for his deportation which included “indulging in unlawful importation of fire arms into the country and dealing in illegal foreign exchange” claims he denied vehemently.

It is interesting to note that at the time of his deportation, it appeared that armed robbery, car stealing syndicates and murders were rampant in the country and that may have catalysed his exit. Parallels can safely be drawn about the current spate of galamsey and the perceived involvement of foreigners happening today.

The Court, in interpreting Section 13 of the Aliens Act, 1963 (Act 160), which provisions are in pari materia with Section 36 of the Immigration Act 2000, (Act 573) found as a fact that Mr Bombelli’s removal fell within the scope of the Minister’s discretion to deport.

When faced with arguments by Counsel for the Appellant that the actions of the Minister – who incidentally was neither represented nor submitted anything to his defence that his action may have breached Article 214 of the Constitution 1979 which is the precursor to Article 296 of the Constitution 1992 providing that:

- Where in this Constitution or in any other law discretionary power is vested in any person or authority,

(a) That discretionary power shall be deemed to imply a duty to be fair and candid;

(b) the exercise of any such discretionary power shall not be arbitrary, capricious or biased either by resentment, prejudice or personal dislike and shall be in accordance with due process of law; and

(c) the person or authority, not being a judge or other judicial officer in the exercise of his judicial functions, in whom the discretionary power is vested shall, by constitutional or statutory instrument, as the case may be, make and publish Regulations, not being inconsistent with any provision of this Constitution or of that other law, which shall govern the exercise of that discretionary power.”

the court acknowledged that the implied legal requirements inherited from the English legal System applied but declined the invitation, arguing that the text of the law did not require the Minister to act judicially in any way:

“Mr Akainyah has argued forcefully that since the minister made allegations of crime against the applicant, the latter ought to have been tried by a court of competent jurisdiction or given a hearing and that he could only have been deported after the observance of due process of law; that he should have been heard before being adjudged guilty of the crimes alleged against him. It would mean therefore that if the applicant was deported for the reasons given in the newspapers and allegedly given by the minister, then the applicant should have been given the chance to defend himself before the decision to deport him should have been made. In other words the minister should observe the audi alteram partem rule before he ordered the deportation of any alien.

It is my view, however, that in ordering deportation, the minister is exercising a purely executive function which should not import any duty to act judicially: see R v. Leman Street Police Station Inspector; Ex parte Venicoff [1920] 3 KB 72.

The court then turned it’s attention to the express words of the Constitution 1979, stating that the matter may require a reference to the Supreme Court:

The order of deportation made by the Minister of Interior should be viewed through the new lights shed by the Constitution, 1979, specifically article 214. This is what counsel has sought and prayed for in this application. His argument boils down to this fact that EI 27 of 1980 was made in excess of the powers conferred upon the minister. What he actually says is that the minister did not comply with the provisions of article 214. This calls for interpretation of that article and its enforcement. By article 118 of the Constitution, 1979 such a function is reserved for the exclusive jurisdiction of the Supreme Court. If counsel’s argument is valid then the matter should be referred to the Supreme Court for determination.

The court did indeed, at the end of the decision made the following references to the Supreme Court:

(1) Whether by the provisions of article 214 of the Constitution, 1979, the minister is required to act judicially in ordering the deportation of an alien; and

(2) Whether an executive instrument is an order within article 4 (7) of the Constitution, 1979, requiring it to be laid before Parliament for 21 sitting days.

The court eventually held in respect of that issue that:

“In times of emergency, it would surely be impracticable to give a hearing to an alien before deportation. I would think that Act 160 gives unfettered discretion to the minister.”

The judicial reasoning in Ex parte Bombelli—that the Minister’s discretion under the Aliens Act or the Immigration Act does not attract a duty to act judicially—was advanced before the 1992 Constitution came into force. The matter was expressly referred to the Supreme Court for interpretation under Article 118 of the 1979 Constitution (now Article 130 of the 1992 Constitution), but there is no record of a final ruling on the scope of Article 214’s (now Article 296) applicability.

If, indeed, the Supreme Court never settled the question, then it remains open to argue that deportation, even when grounded in ministerial discretion, must comply with the constitutional guarantees of fairness, non-arbitrariness, and audi alteram partem. The constitutional imperative in Article 296 is categorical: all discretionary powers must be exercised in accordance with due process.

In the absence of a definitive interpretation, the jurisprudence remains unsettled. Thus, there is a credible legal basis to contend that deportation—whether ordered post-conviction or based solely on executive discretion—must afford the affected foreign national an opportunity to be heard.

The stark reality of two non-citizens committing offenses yet facing vastly different deportation procedures – one potentially expedited through ministerial discretion without full judicial process, particularly if the alleged offense involves ‘galamsey’ or cybercrime, while the other benefits from judicial safeguards – reveals a troubling and discriminatory application of the law. This disparate treatment not only undermines the principle of equality before the law but also casts a shadow on Ghana’s commitment to justice and fairness for all individuals within its territory.

To ensure adherence to the rule of law and protect the rights of foreign nationals, it is recommended that the government develop clear guidelines for the Minister’s discretional power which guarantee due process for all.

[1] Defined fully in Section 8 of Act 573

Yaw Nkansah Abankroh Esq.

0558789982